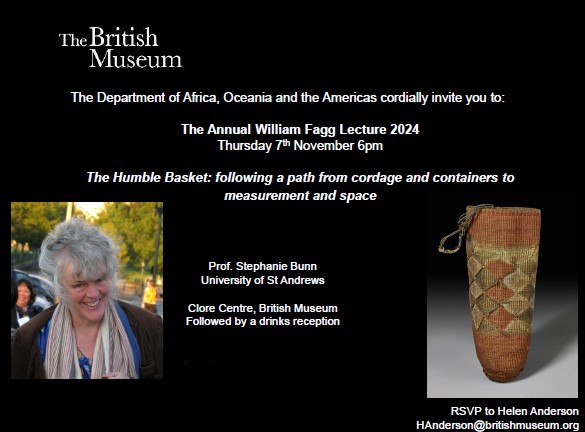

The Humble Basket: following a path from cordage and containers to measurement and space

Prof Stephanie Bunn, University of St Andrews

The invention of string, baskets and related forms of weaving is told in countless creation myths, from the invention of string by the Wawilak Sisters, Ancestral Beings in Northwest Arnhem Land, to the discovery of Yekuana baskets by ancestors in Amazonia, and the creation of Dogon granaries in Mali. These woven artefacts hold a significant place in human cultural development.

The Ancient Egyptians used hemp rope to measure boundaries. Groups in South America made grass cords held together by tension and friction to span the straight-line crossing of a canyon by the Q’eswachaka bridge. Folds in a palm leaf basket from Papua New Guinea create three dimensions from two. Plaited bamboo containers from Borneo use decreasing strands to create the positive curvature of corners and increasing weavers to create the negative curvature of brims and surface decoration.

In all the techniques and plant materials used in making basketry there is a unique geometry, a use of space, a sense of proportion and a knowledge of form that creates structure and stability. Through the intertwining of bodily skills and plant materials, alongside the emerging artefact arises a kind of mathematical knowing, an implicit structural comprehension of how things hold together through tension and friction; what techniques can produce strengths that will carry weights, or stretch that will allow them to expand; how to estimate proportion and balance – an understanding of the patterns and strengths of the world.

Making structures such as containers, cordage and traps is a skill that has both generated and regenerated human culture broadly within communities, and human cognitive processes within a person. Put simply, basketry is one of the skills that has made us human. It has both created forms, techniques and structures which enabled human development, but its very practice has also developed our human capacity and ingenuity for change and knowledge creation. From containers and transport to adding machines and computers.

This William Fagg lecture highlights the geometry in basketry and related structures which illustrate the significance of basketry for human mathematical development. The story is told through the baskets themselves, from a Japanese folded ‘origami’ basket from Kew Gardens’ Economic Botany Collection, which reveals the link between basketry and Platonic forms; a cycloid weave backpack from Sarawak, now in the British Museum, which reveals the potential of cycloid weave for creating hyperbolic surfaces; string samples from the Pitt Rivers Museum which highlights the skills employed in creating a simple line; a decorative belt from Sutton Hoo which explores group theory….and many others.

The event is free, but places must be booked. RSVP to Helen Anderson HAnderson@britishmuseum.org